Investing in Art - The Art of Investing

We create art collections

Art Consulting

Arranging art collections

Cataloguing collections of works of art

Consevation of works of art

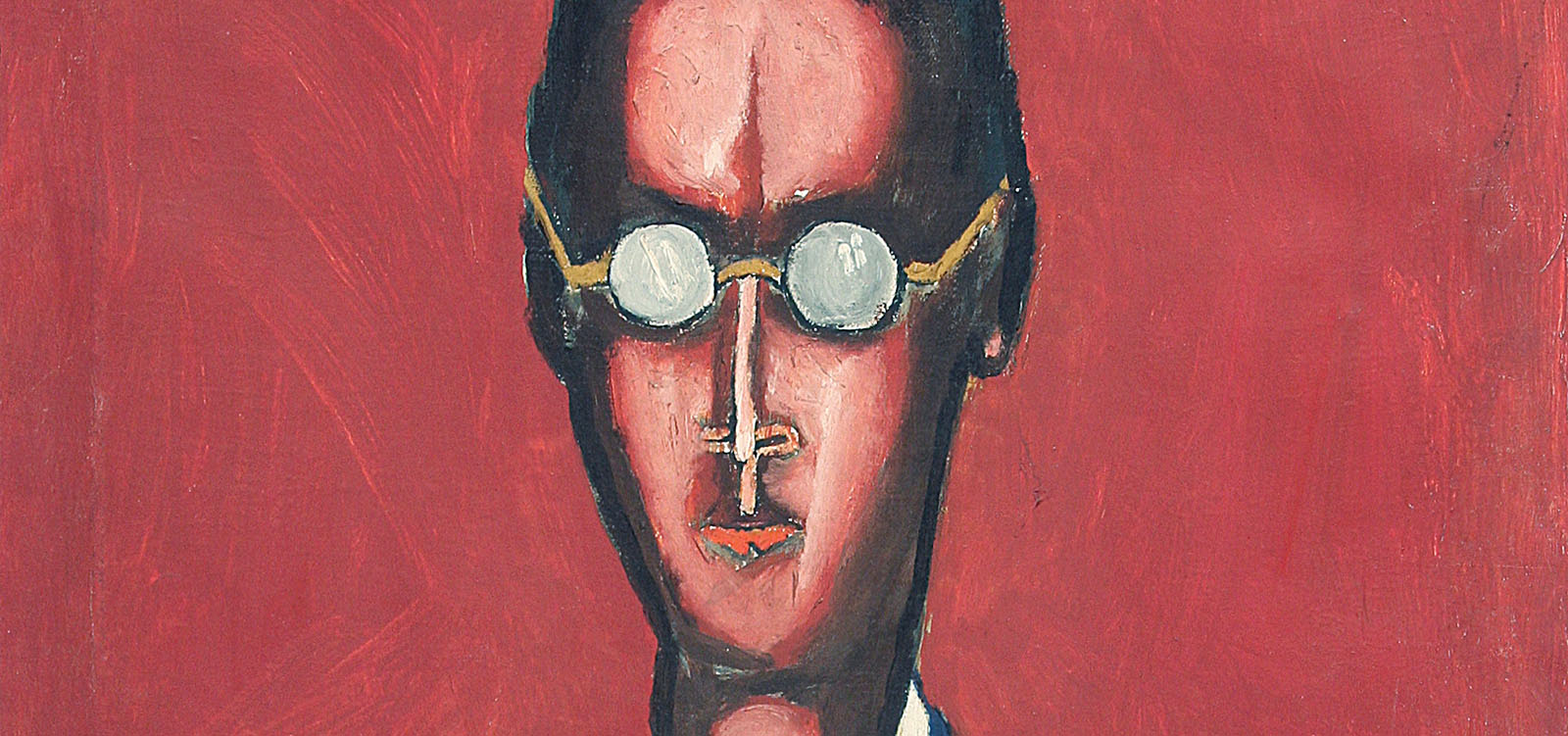

I cannot write about Stanislaw Batruch's painting from the position of a wise man, equipped with a magnifying glass and an eye and an elaborate apparatus of art criticism's terms. I was equipped at the university with an apparatus to act as a wise guy when literature was concerned. Why do I then get down to something I am not officially an expert on? I feel justified by the fact that no artist paints for critics, but mainly for those who feel like he does, who feel together with him. I have been watching Stanislaw Batruch's painting for three decades from this position - of the audience feeling alike.

Stanisław Batruch's way to painting was not a straight one. He was born in

These two years of such "pre-studying" are good if one wants to be sure of his choice of the future career, furthermore they give one more self-confidence. Because you already have a diploma. A diploma of a qualified teacher of a primary school. Just as his parents had wanted from the beginning. But Batruch decided to make another attempt at the real studies in painting. This time it was successful. He was then twenty-five years old. He studied at the

After graduating, he first became a teacher of painting in Liceum Sztuk Plastycznych (Secondary School of Graphic Arts) in Krakow - so he made good use of his pedagogical training - and for some time was responsible for the student culture in the Regional Council of the Association of Polish Students in Krakow; then he became an assistant teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts, where he now works as a professor and runs a painting workshop at the department of graphic art. But before he began showing his paintings in art galleries, together with a group of his friends, painters and sculptors, he had organised open air actions, which we would now call installations, devoted to the issues of environmental threats. It was just after the General Secretary of UNO, U Thant, made an appeal on environmental protection, and much earlier than any ecological movements arose in

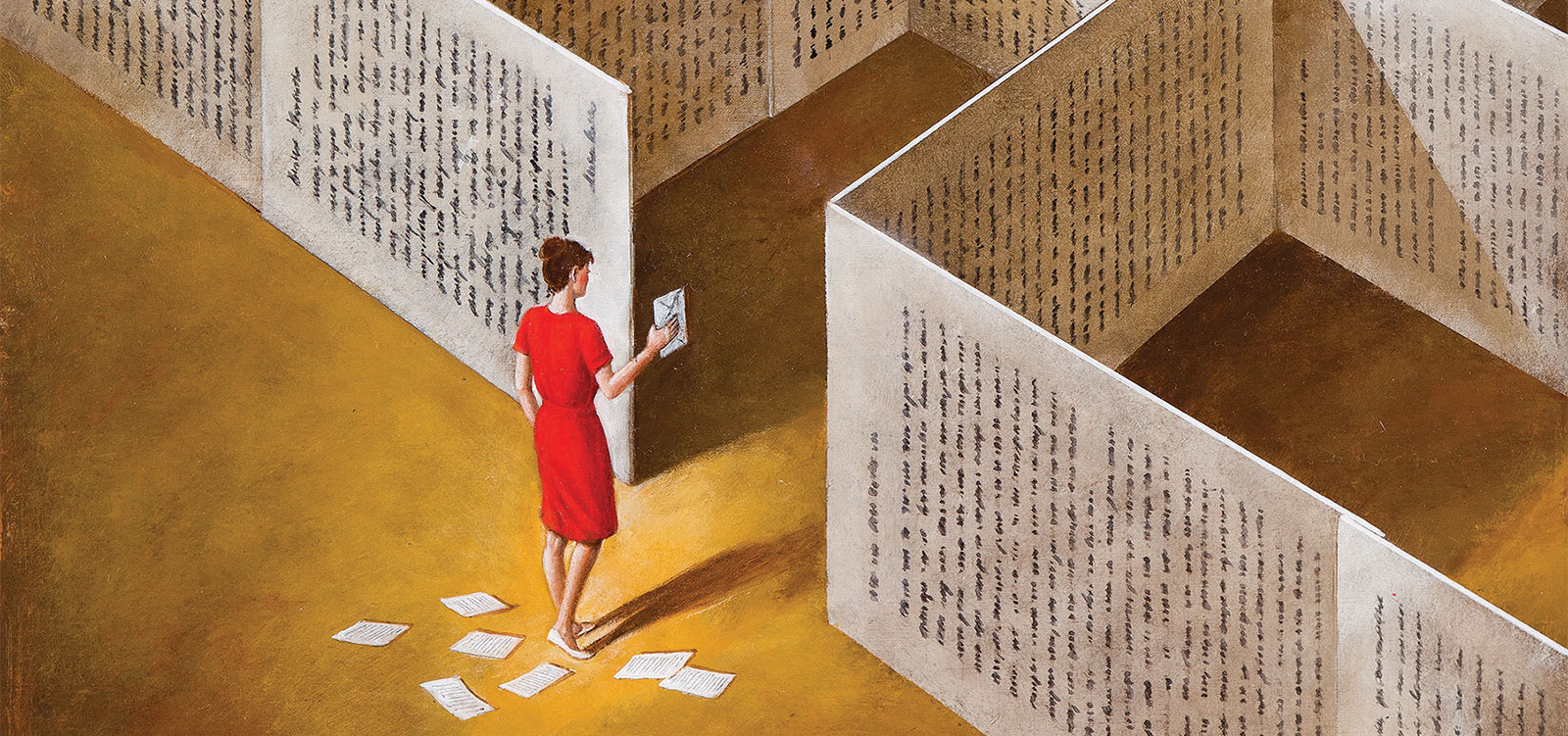

At first he painted - as Stanisław Rodziński wrote in a sketch on Batruch, published some time ago in "Nowy Wyraz" - "landscapes and compositions, correct in colour, nicely constructed, in which the experience of abstract painting ordered the observation", but with time, as Rodziński concluded, Batruch got rid of "sprightly anonymity, which is a popular sin of works made just after graduation", and started to treat art as a form of conversation with man and meditation on the righteousness of his life and work. That was how Batruch formulated his early programme in an introduction to one of his works. Then he began searching for a sign, a symbol, which would order our surroundings. He ordered the world. The phytagoreans thought that a number was a symbol encompassing the whole world. There is a picture from the seventies, entitled He saw (Przejrzał). It consists of numbers and mathematical symbols: adding, subtracting and equation, but behind them there is a man with a stretched out arm. In his search for the symbol, through numbers and road signs, Batruch finally reached the human figure.

Several years ago, when he still had his studio at

Then I have watched other versions of this theme. Once it was a man rolling a rock onto the top of the mountain, some other time a group of people in front of and behind a barrier, a jumper doing an acrobatic pole vault over the white and red vault, a man crushed with the weight of a crucifix. Every time it was a man confronting a challenge, a barrier to overcome. A Sisyphus. Yet I have always seen in Stanislaw Batruch's Sisyphuses a Sisyphus of Albert Camus, a hero of its difficult humanistic existentialism. That is someone who is aware of ineffectiveness of his efforts, but still makes them. Even more, he makes his absurd effort with a smile.

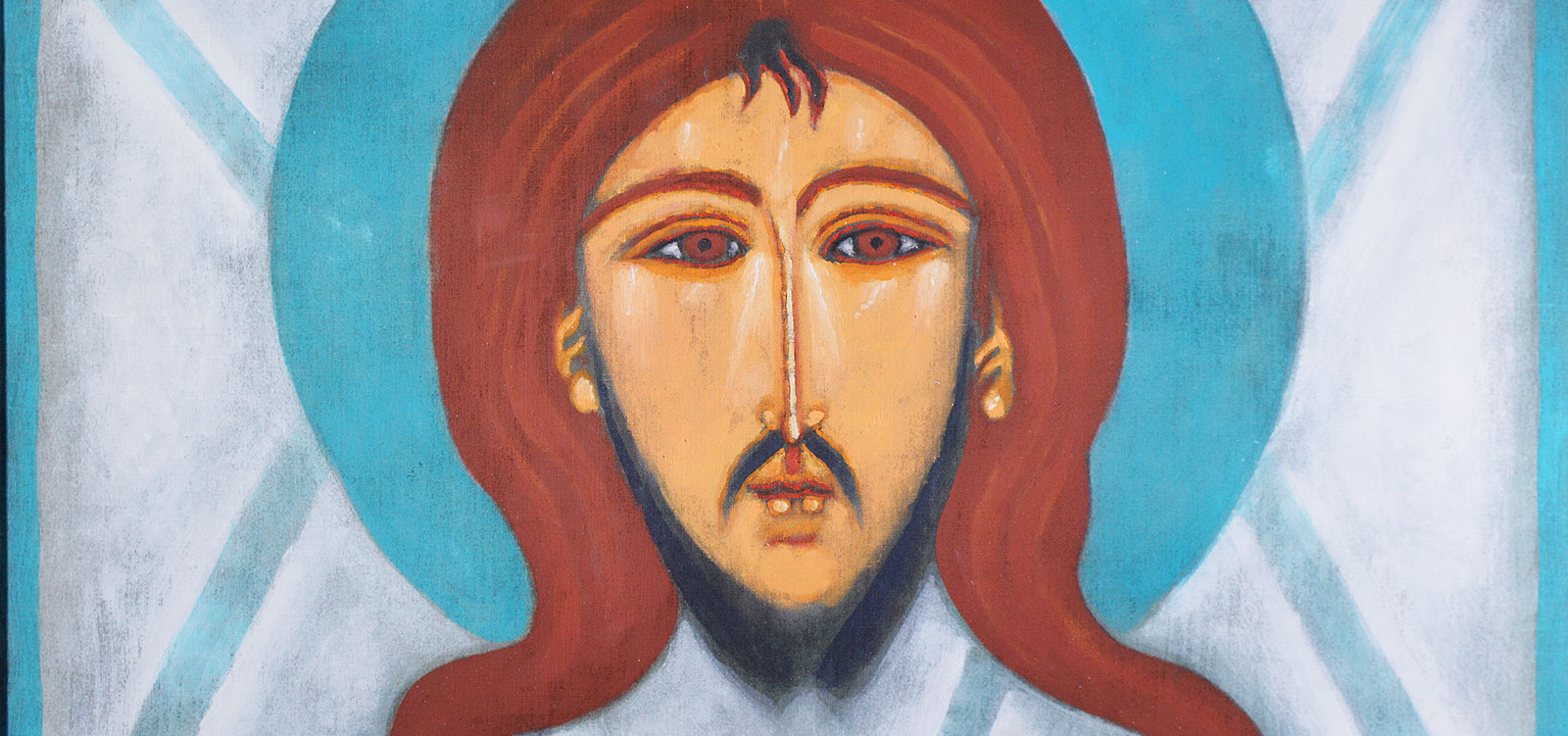

In Stanisław Batruch's artistic activity there are some pictures constituting a series called Processions (Procesje). In one of them, entitled In the door (W drzwiach), a group of people is walking towards an open door seen in the background, with strong light showing from it. Some students of one of

Once I met Stanisław Batruch in his studio, painting a proud bullfighter. A bullfighter El Greco could have painted. "Isn't it not modern enough?," I asked. "I don't like that word," was the reply. "There are various charlatans using that word. I prefer the term . Some people, when asked about the difference between the modern and the contemporary, say - and I agree with them - that the modern grows old fast and in an ugly way, like Jerzy Stempowski wrote, and the contemporary is catching up with the times. So it does not grow old.

Let us leave aside the labels, they are the ones to grow old first. Stanislaw Batruch's painting from the turn of the seventies and the eighties corresponded with the high temperature of the discourse of those times. It had this "publicist" or "social" character, to use again the key words. It was anthropocentric, because in its centre there was always a man with his complicated relations to the present time. It was the time of paintings with people standing in front of barriers, trying to overcome bars in a jump. And always these symbolic barriers to overcome are painted in a white and red pattern. People are neither abstract nor realistic. They are without faces, but often recognizable. You do not need to strain your imagination to see in them a physical resemblance to some political or artistic VIPs of those times. The artist, when asked whether this was intentional, hides his answer in a smile under white moustache.

On one of Stanisław Batruch's paintings people are standing in front of a border barrier with bundles. One of them is carrying a crossed painting-easel. It is a commemoration of the exodus of hundreds of thousands of people from

A rebellion against limitations of freedom, against the subjective treatment of man, a fight with conductors, a bitter taste of loss, all these can be found in a series of big paintings entitled The Conductor of Ballet (Dyrygent Baletu). At its beginning, the conductor is monumental, and still some participants of ballet cannot even see him, because they are covered with a huge red sheet. In the last pictures, the conductor is just a scarecrow. But also those he conducts have shrunk from fear and are going in circles in a "straw-cover dance". The only lyrical element is a bird sitting on a raised arm, in which the conductor holds his baton.

This bird is a forerunner of the lyrical period in Stanislaw Batruch's painting, which came as calming down after "Sturm und Drang". I think Professor Ryszard Hunger had mainly this period in mind when, in connection with the process of giving Stanislaw Batruch a title of Professor of Graphic Arts, he presented Batruch's artistic activity in these words:

"Stanisław Batruch's painting is characterised by strength, which comes from a deep conformity between the artistic vocation and the direct contact with reality. The theme of an endangered and persecuted man, the tension of living in a crowd, threats to the human values - all these can be found in Batruch's paintings, transformed in an original way, in which colour and its specific materialisation are decisive. We can see a convergence between the world of emotion and the abstract world of thought. Between the painter's affirmation of reality and his doubt. Closed figures, deeply human, constitute a gallery in which an emotion is never degraded to the banality of sentimentality. Compassion is never enough for a justification, the appeal to human conscience is not just a simple protest. This is humanistic painting, created wisely and with feeling, grown from poetics, at the same time touching contemporary dramas. It does not, however, draw from them the need to negate and destroy".

In May 1990 Stanislaw Batruch received a prestigious award of the Volker Heitland foundation, awarded in

The ceremony of granting the award of Volker Heitland foundation, together with the artist's exhibition, took place in a castle in

Then came a new period, full of concentration, but also of quietness. It was announced by landscapes from Mirabel, where Stanisław Batruch has been going with his friends from the creative group "Blue Rose" (Błękitna Róża) for open air painting together with artists from "New Darmstad Secession" since 1981. There is in these landscapes the red soil of southern France, deep green (someone has called Batruch a master of deep green) of Provance vineyards and cypresses planted alongside roads which remember the times of Caesar, and the cloudy greenish sky. The one you can see there in the south for a few hours before mistral begins to blow. The wind that drove Van Gogh crazy. Looking at those landscapes I recall the smell of thyme and other herbs growing on the edges of vineyards. We used to pick handfuls of them and to bring them home and let the smell fill the whole house. Batruch's paintings from Mirabel also have the rough surface of ground. I like touching them. Just as I liked taking a handful of this red, southern soil and feeling its warmth and life-giving force.

In a new period of Stanisław Batruch's painting Sisyphus' dramas are replaced with a man in a landscape and a landscape itself. But it is not a smooth idyllic landscape, or a sentimental one. It is just that the shape which used to dominate in the picture is now replaced by colour. The place of old subdued colours - greys, blues, black, browns and purples is now taken by bright green, bright yellow, bright orange. Yet the paintings emanate with peace and order. Professor Ryszard Hunger sees its source in the exceptional ear for colours that Batruch has (I like this poetic description: "ear for colours" very much), "which even in risky juxtapositions lets you feel the refined taste and in the accepted composition discipline, which protects from any incidentality." It happens in the painting In the field (W polu), where two women are walking in the field, with some trees marked on the horizon. Or in The Sewer (Siewca) strained under the burden of seeds or in The Plougher (Oracz). Although they are stylistically connected to the previous period, there is no dramatic tension in them. Though in Jurassic Ghosts (Strachy jurajskie) from 1991 we find the same motif as in The Conductor, older by twenty years, but Jurassic Ghosts, contrary to The Conductor are full of peace and order. It is a result of a different treatment of man. Is it not a kind of comeback, I have recently asked Batruch, while looking at his latest paintings in his studio. Yes, it is a comeback, but in another formal construction, the artist says. Formerly I used crude planes and decided symbols. When I painted, say, a barrier, it was decided, defined, and though it was white and red, it was universal. The universalism of that symbolism in my painting was even emphasised in the justification of the Heitland award. The German audience was not interested in possible connotations to the Polish political situation. Each person related it to another, yet universal, situation. It concerns all artists who use symbols. When looking at The Disasters of War by Goya or Picasso's Guernica we do not see the illustration of the specific historic situation, but a general symbol of the atrocities of war. When I am now painting a picture entitled Fight for a Chair (Walka o fotel), some people will relate it to the contemporary situations, but I am doing it in a different way, more in a painter's way. I use such juxtapositions which must be characteristic of a painting. Earlier it did not matter to me, because I was more concerned with the idea than the technique. This purely painting technique. And now it has changed and I pay more attention to putting this here, that there, that there must be a contrast. To sum it up, now I tell stories more in a painter's way.

But now, I paint landscapes more often, Batruch says. Actually I have been painting them all that time, but in the context of my painting showing the Idea - landscape seemed to me somewhat not serious, even funny. Then I painted landscapes as an exercise and not pure expression. But I see that it was no reason to be ashamed, because it is a large part of my painting activity. Besides there are new experiences - my foreign trips, to France, Italy, and... coming back to my home land, the land of my childhood and puberty, to Beskid Niski. There are Lemko's Orthodox churches. I come back there with some sentiment, because I was taught painting by that sky, by that woods. I always come across something new there, which would have escaped my attention earlier - a flash of sunshine on the river, a gleam of fish in the brook. Now these things I did not pay attention to before, because they were so obvious, are seen more clearly. Thus the topics of my painting have made a circle, I am almost at the beginning again, where my roots are. But this is another beginning. Just like in a spiral, I look at the same place, but from a higher position.

His even later works: Secret Garden (Tajemniczy Ogród), Harenda, The Old House (Stary dom) or a series of autumn landscapes from Jura Krakowsko-Częstochowska are totally different in character.

When writing a few years ago a text for Stanisław Batruch's painting album, I concluded with a question whether Stanislaw Batruch's painting was breaking the closed door, demolishing walls and opening new perspectives in painting? I could not then and cannot still answer that question. Let it be. I would like to answer yes. But I will just say like then that it is like with Norwid, who wrote about his poetry:

My son - will pass by my writing

But you will recall it, grandson

So I guess that only our descendants will answer that question.

Franciszek Palowski