,,… I achieved a great success in Lucern. One morning I started to paint as early as sundown, sitting on the edge of the pavement, and I finished when the sun was high and the traffic heavy. A group of young English ladies surrounded me so that nobody disturbed my work. When I finished they asked if I would sell my picture and how much I would want for it. When I aksed 20 franks for it they started to bid the picture among themselves, and when I finally handed it over to one of the girls, I got a handful of gold in return. When I calculated it, it turned out to be 100 franks. In spite of my surprise I did not protest. They themselves decided this was the value of my picture…”, remembers the best Polish painter in water-colours, Julian Fałat without commenting this event further.

What a shame that he did not since it event deserved reflections. Namely, those English girls paid attention to a water-colour at the time when this technique held in contempt in Poland. Water-colour was considered to be easy, even childish due to the absence of technical intricacies, and suitable for amateurs and young ladies rather than for professional artists who were allowed to use it for entertainment only or for some inferior purposes like making sketches or adding colours to drawings, in other words filling linear contours with delicate and translucent colour. In the way that Federigo Zuccaro recommended in his letters.

Those young British ladies had quite a different opinion on water-colour, which is not surprising considering the fact that the technique came into being in England where eventually the true art of water-colour painting was developed, soon to become the national specialism and pride, and a subject taught at the Royal Academy of Water-Colour. In the Academy there were active such outstanding representatives of this technique as Paul Sandby (1731-1809), J.R. Cozens (1752-1795), Thomas Grittin (1775-1797) and, first of all, J.M.W.Turner, whose pictures woven of coloured mists fascinated future Impressionists during the French-Prussian war and contributed to the development of the trend, perhaps the artistic philosophy, which is still alive today. It is impossible not to mention also the Post-Impressionism John Constable (1776-1837) who was equally famous, and their followers, including such great painters in water-colours as Sel Cotman, David Cox, Towne, Varley and de Wint.

The situation was different in Poland. The only serious painter in water-colours in those days was Piotr Michałowski, who did not sell his works in the country, so consequently was recognized as an eccentric amateur. Contrary to France, where prices of his works were as high as Delacroix’ ones. This was so surprising for his friend at banishment that he wrote in his letter:” Piotruś is paid as much for his painted horses as he has never got for real ones at home!” On top of that, they were painted in water-colours! They must have been crazy in Paris!

In the middle of 19th century the public in Warsaw divided pictures into two classes. The first one, which was considered superior and respectful, included religious and historical scenes, portraits and copies (!) of great masters. The second inferior one, included landscapes, still lifes and all water-colours irrespective of their subject matters, because water-colour was treated as a preparatory, fast and easy technique, useful for making sketches or other “notes” in plain air to be used in studios as bases for oil paintings, that is for Works of Art suitable for gold frames and deserving a prominent place at home.

Painting in water-colours is a difficult technique, perhaps the most difficult among different types of painting, and abundant in possibilities. The difficulties source from its greatest merit and charm, namely from the lightness and luminosity due to the transparency of paint. Water-colour does not cover the background irrespective of material on which it is made, be it paper, silk, velvet, canvas, wood or ivory. That is why it should be remembered that material is of equal significance for the appearance of work as paint. Paper comes in a great number of kinds – it can be smooth or rough, in bright white or cream shades, with visible threads or no. It can range from the most expensive linen or cotton to poor, yellowish type which turns into sawdust, like paper of the Socialistic epoch.

The first decision of a painter in water-colours concerns the choice of proper paper for a particular artistic plan because some concepts require special varieties of paper which cannot be found in shops. The second decision is the choice of a method as this “simple”, even poor technique, as the public tends to believe, is in fact varied and extremely complicated. The basic tool is an elastic and sharp brush preferably made of the badger’s or the Siberian mink’s hair since the best ones of the beaver’s or the otter’s hair are not available in the market. Finally, a brush of hair from the ear of the red ox could also do. A brush made of the squirrel’s hair is not acceptable because the hair is too flabby. Moreover, a painter in water-colours should have at hand a sponge, a soft rubber to remove traces of pencil, a little bowl of white china and a hair-dryer. As soon as he is equipped like this, he can start working. He has two basic techniques to choose from. Namely, he can put wet paints on a dry paper or wet paints on a wet paper, or use their combinations. Additionally he can enrich painterly effects applying grains of salt or sand, or, like great Emil Nolde, allow his water-colour to be exposed to snow or drops of rain. He can also paint with the use of a concealing liquid or candles and hard cheese, or….

There are many different possibilities and every artist has his secrets which he enviously safeguards like a medieval alchemist, careful not to let anybody see and learn his artistic manner. Contrary to a general opinion, not every colour spot in a water-colour is final or impossible to correct. A water-colour can be altered and improved. It is also possible to cover one colour with another provided that one has a perfect knowledge of the character of particular pigments and their saturation. But first of all a painter in water-colours should know how to avoid dirty smudges which disqualify any work. One can also rinse a water-colour to achieve luminosity and to soften contours. One can paint on coloured backgrounds and glaze a water-colour to achieve solid tones, scratch the surface to obtain the effect of light, stamp pieces of fabrics, spray paint with the use of a toothbrush and paint on paper covered with a 1-milimiter layer of water.

The above information seems lengthy but it is necessary to understand the wide range of possibilities of expression and technical complexity that water-colour offers. It enables us to realize the unknown truth that water-colour is a flexible and versatile technique full of nuances. It is a technique which can successfully compete with allegedly more perfect oil painting and tempera, which were employed by great masters of the Middle Ages and of later epochs.

In reality, water-colour may be a match to oil painting as regards the harmony of colours and their depth, and to allegedly peerless egg tempera as regards their purity and luminosity. Consequently, a painter in water-colours may choose from the whole range of possibilities starting from thick, gloomy and heavy painting to chiaroscuro painting in which effects are achieved with the use of “light on dimness” or “light on light”. The latter one is probably most difficult but, at the same time, most attractive. Its precursor was Rembrandt who used this technique to paint his “Captain Cox’s company”, later named “The night guard” when the paints got dark, and his “The Batavians’ conspiracy against Claudius Civilis”. Rembrandt had many followers, including Luminists, the above mentioned Turner and Impressionists.

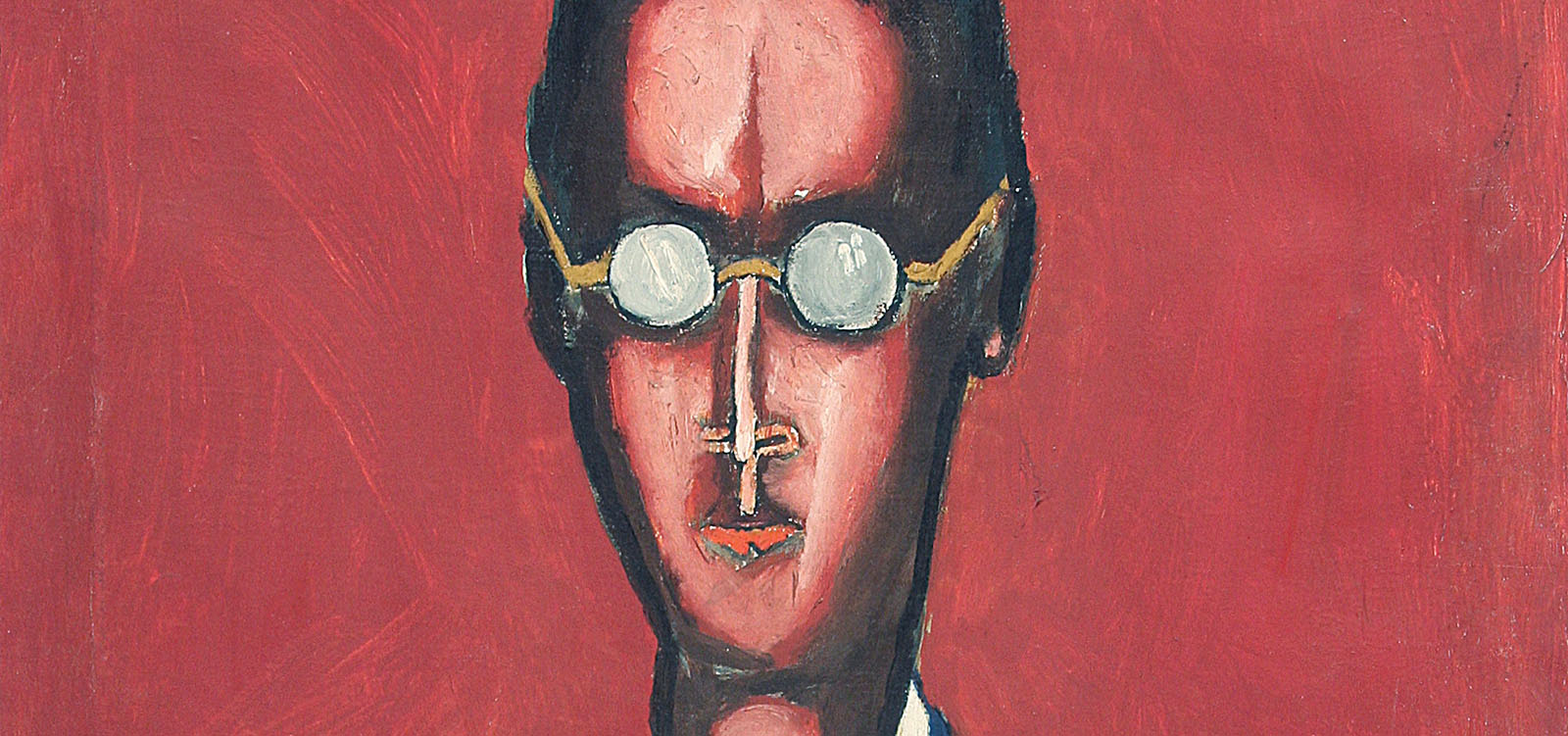

Józef Stachnik’s art, together with accompanying philosophical implications, stems from this source. He is a painter of landscapes. This seemingly limited motif allows him to express his view on life. The motif is only outwardly limited because in essence it offers a full range of expressive possibilities. Through a landscape one can show that the world is sinister, incomprehensible and full of dangers. One can also demonstrate the insignificance of a human being against the power of nature and destructive force of the elements. It is possible to suggest that the world is mysterious and its governing laws cannot be fully grasped by human mind. It is not without a good reason that the eerie aura of Surrealism sources from de Chiric’s, Dali’s and Tanguy’s landscapes which are endless and loathsome in their deadness.

Józef Stachnik’s world is good, safe and comprehensible. It is almost the ideal world, beautiful, warm, filled with daylight, deprived of shadows and gloom. Besides, his is a material world. The sky, which in art is a synonym of the sprit and spirituality, plays an inferior role of a background. It is present in his landscapes but the line of the horizon is never lower than in the middle of picture. More frequently the sky is visible only through openings in thick tree crowns, and sometimes it is obscured. Particularly when Stachnik paints one flower or a different fragment of nature viewed from the bird-eye perspective.

His landscapes are “clear” views because they are deserted. When a man appears in them, he always plays the part of an accessory only; he never appears as the main or an equivalent motif.

Man’s works, including architecture, draw more attention than man himself. It is both old architecture, painted with nostalgic sentiment, and modern one, including colossal structures of New York, which fascinated the artist during his visit to the United States. The artist seems to prefer and understand the order and rhythm of simple lines introduced by man more than the chaotic charm of nature, which in his works usually only complements and emphasizes by contrast the perfect regularity of proportions, and vertical, horizontal and slanted lines. Thus he uses the symbol of man’s dominance over nature, unchanged throughout thousands of years, which manifests itself in the geometry alien to nature.

Stachnik is masterly in using the whiteness and transparency of water-colour paints, that is the greatest trump cards of his favourite technique. Light is reflected by the whole area of the picture thus endowing it with Turner-style delicacy, resembling Japanese Ukiyo-e which are records of what we can call the emanation of the matter and the transposition of physical concreteness into the world of ideas and pure notions. Consequently, the artist frequently paints not an object but its volatile and immaterial idea, not a thing but his idea of it. He must do it in an intuitive rather than an a priori way because he sometimes uses massive spots of colour. Particularly in the foreground, which gives depth to his compositions. Stachnik is able to compose his works efficiently and easily. The format of his works which are almost perfect squares, resembling film frames, are conducive to it. Only sometimes does he use an extremely difficult format of an elongated rectangle, and then only in a vertical and never in a horizontal position. He is clearly drawn by verticalism in all varieties of rhythms which organize the plane.

One of typical characteristics of the artist’s work is that he creates cycles, portraying one place or studying and documenting one motif such as country mansions or halls, small wooden churches, botanical gardens in the US or Krakow, or rocky shores of Sicily. He likes landscapes in snow although he most gladly wraps his architecture in delicate spring-fresh verdure. We can also add that that Stachnik paints with an evident pleasure and shows liking for motifs. His joy spreads to us, viewers of his water-colours.