Investing in Art - The Art of Investing

We create art collections

Art Consulting

Arranging art collections

Cataloguing collections of works of art

Consevation of works of art

"When is a painting good? - asked Renoir and gave himself the answer immediately - for me the picture must be something pleasant, merry and pretty. There are enough ugly things in the world to create new ones..."

A lot has changed since his times. The era called "beautiful7', la belle epoque, the era in which he lived had passed. The breathless twentieth century came, the century in which even the joy developed an unprecedented pace and maybe even a rush; aren't the dancing twenties with their jazz band, Charleston and the frantic art deco movement called "'the crazy twenties"? Maybe all our century will seem some time in the future crazy with its art which developed as a visible sign of the state of people's minds, that is generally speaking - conscience. Only then will it turn out how few of its artists decided to react spontaneously, to make a full, unrestricted and sincere expression. Or maybe in a different way - they could indulge in it and as many of them took to heart the words said at the beginning of the century that is just about to end: "art has to pull faces at sophisticated connoisseurs and cannot be". That's the point, what cannot it be like, as already at that time it was able to abolish taboos and hurt feelings, challenge all kinds of beauty, and then as in conceptualism, even really existing, material creation?

Well, it seems that our century's art cannot be spontaneous or impetuous unless it accuses or threatens, unless it wants to disturb people's minds or climb the pedestal of the world's morality.

Krzysztof Kuliś does not want to judge it. Just the opposite, he wants to praise or venerate its beauty and all, even the simplest charms, which are so precious to his masculine heart. He wants to notice and express all his colours and hues in the most literal sense. All, except for those dark, sombre and as a result, unpleasant ones.

His painting is - if to use the slogan from before the War - healthy and full of stamina, since "healthy spirit in a healthy body" - which is suitable for this mixture of optimism. It is maybe even a bit pageant since weren't they pageants who coined this saying as a sign of their spontaneous approval of existence.- "as long as we are - there is no death - when there is death - we are not there"?

In the art made by Kuliś" there is no death, or even a premonition of its existence and inevitability together with everything that this term implies and it is in fact a very broad one.

Krzysztof Kuliś observes and transforms in his own imagination of a painter and in his own temperament (wasn't it Zola who said: "landscape is nature seen through the artist's temperament"?) all charms and colours of the world. Whereas the colour and its arrangements are expressions of a feeling, or its higher and hotter variant, which is emotion.

Also this word is full of tinges. Sometimes emotions are intense and violent, as the composition of the most contrasting with each other complementing colours, or romantic and reflective, as a toned monochrome. Sometimes they are dynamic as the line's vista, noting a spontaneous hand movement and prolix as a soft spot. Sometimes they are saturated with the uniform light of the south and basking in the stormy light-and-shade effects. Still, they are always saturated with their own brightness, since isn't the light alike the colour to the same degree as it is the carrier of feelings, as it expresses them and passes to others?

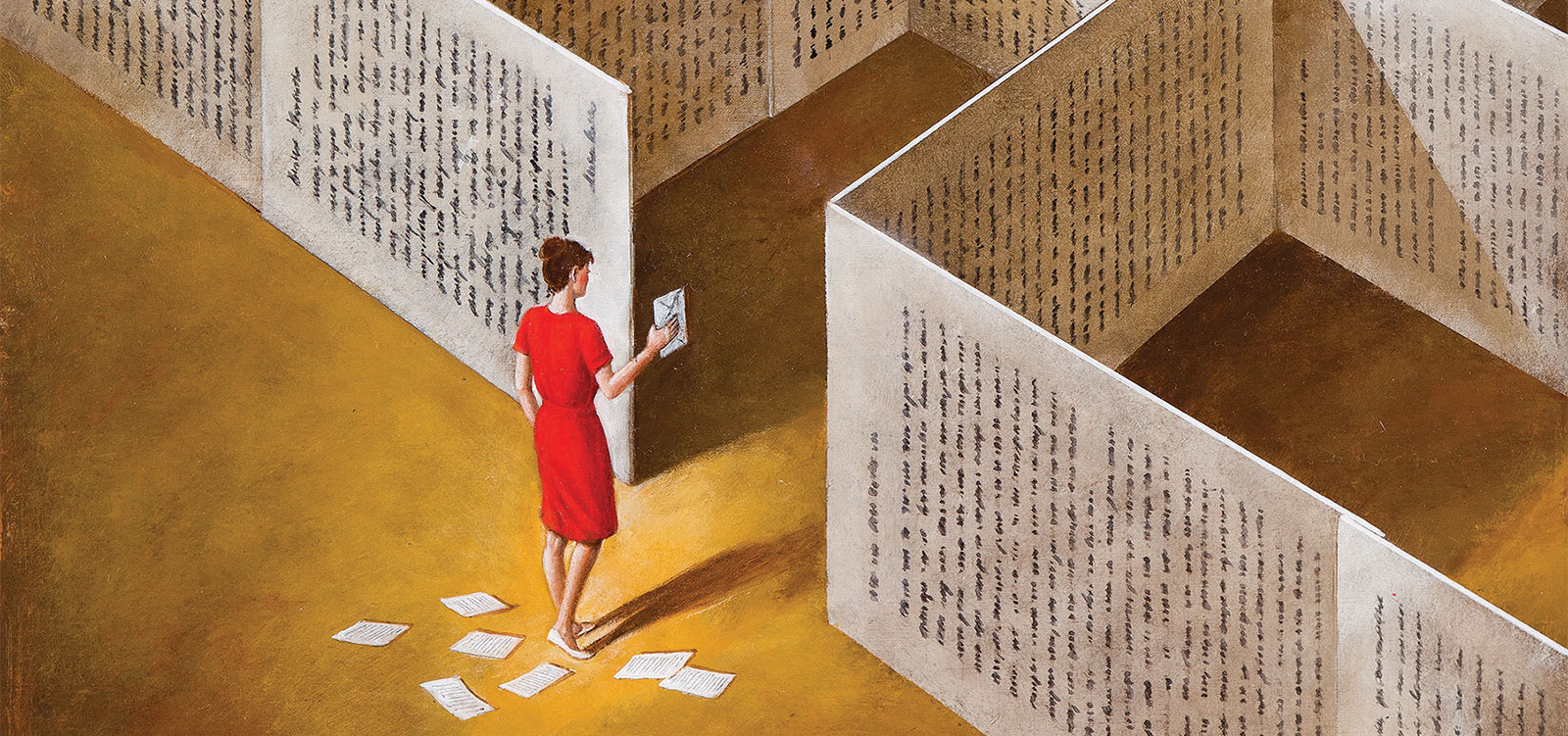

Paintings by Krzysztof Kuliś amaze with their variety which is so enormous that sometimes you get an impression of being in the company of a few, extremely distant from each other, although equally strong personalities: of a gentle poet in sophisticated, light water-colours together with their tendency to being static and amor vacui and sometimes very advanced synthesis of shape and scale, or an unscrupulous expressionist with typical of this trend horror vacuum, fear of emptiness, of leaving at least a patch uncovered with a tangle of spots and lines of the plane.

Thus, we have to do with a contemplative artist who wants to make us meditate and such an artist who tries to impose on us his point of view or even force us to look at his reality or at least its fragment through the prism of his emotions. We have to do with an artist who wants to tell us - look how it is possible to magnify the ambience drowsing in one prosaic landscape, how it is possible to get it to the edge of explosion, to the edge of bursting the creation by colour arrangements and tension of the composition with the strength of critical mass.

In such situations we usually talk about rich personality. Indeed, Krzysztof Kuliś has a complex personality and is able to express it in his paintings.

A separate chapter, or a motive in his creation is a theatrical cycle, and other mini cycles of all features of stage-setting (and the artist knows all about the theatre, in a way, he knows is "from the inside") in "Park Bench" style. They are figural and in a way monothematic since linked in one whole by the character of a naked or half-naked girl with rounded hips, appearing in all the works. Her personality appears both in "Dziady" ("Forefathers") by Adam Mickiewicz and in "Niemcy" ("Germans") by Leon Kruczkowski, therefore also there where she was not intended by the authors.

Thus, in the spectator's eyes, this true-born girl changes into a symbol of senses and sensuality, becomes a personification of sensuous nature, unrestrained by any, even the least favourable circumstances.

That's exactly the painting by Krzysztof Kuliś: unrestrained, sensuous and not taking into consideration the fact whether it is going to please anybody or not. That's why is may have, and does have, its fervent supporters and equally uncompromising enemies, but leaves nobody indifferent. And this is what best expresses its calibre.

Jerzy Madeyski