Investing in Art - The Art of Investing

We create art collections

Art Consulting

Arranging art collections

Cataloguing collections of works of art

Consevation of works of art

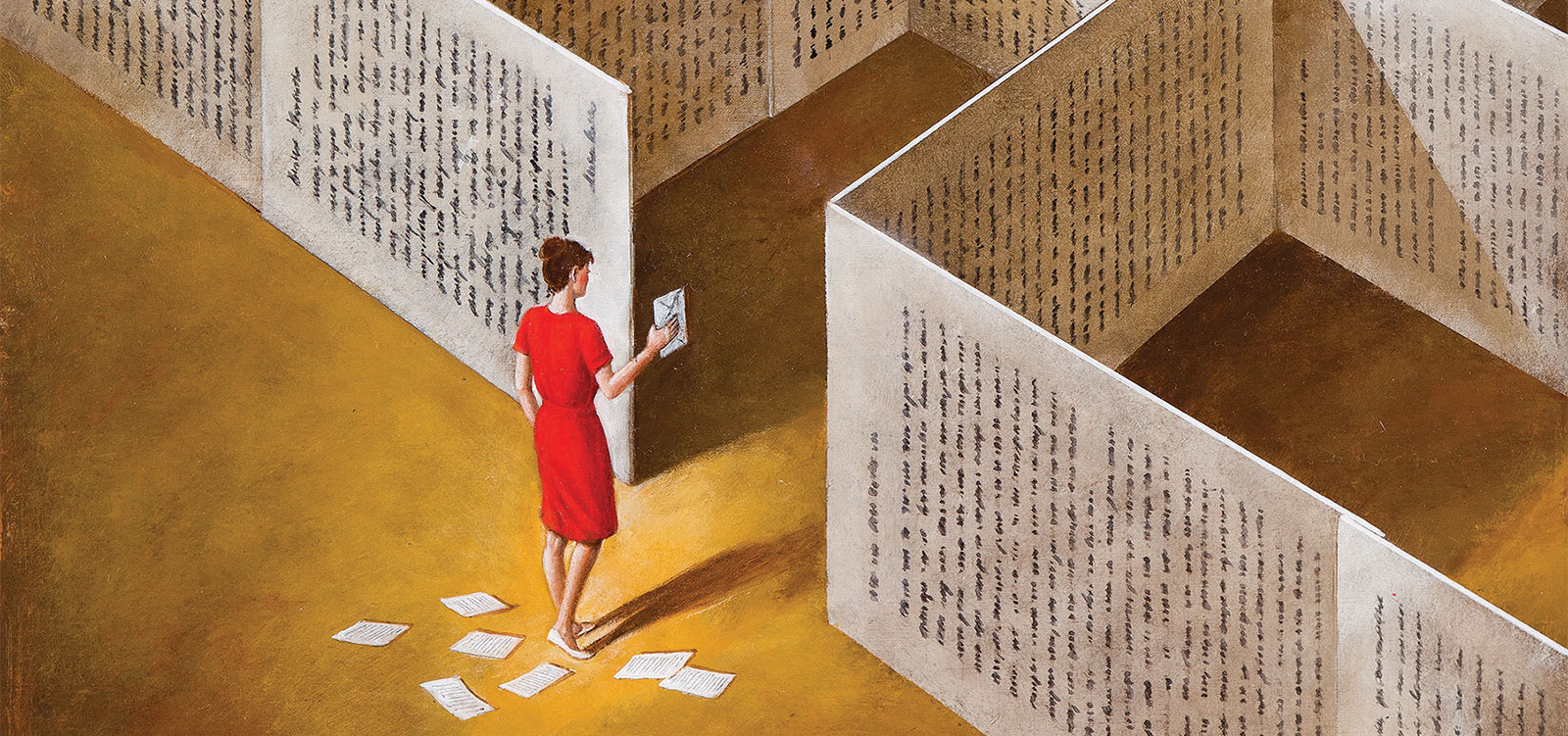

We live in an age of suspicion. The appellation, "age of suspicion," was coined in the middle of this century by Nathalie Serraute, the distinguished French writer and essayist. Suspicion is otherwise distrust, disbelief, doubt. We trust neither ourselves nor the world, neither civilisation nor art. This is because we do not trust life to be either logical or sensible, clear or conscious. It became apparent that all that we were building only becomes nourishment for dark and destructive instincts. Thus we doubted the certainty of any given. Even art, which after all is supposed to be the emanation of the superior side of our being, has with time ceased to believe that it is in a position to save or even strengthen anything. With an energy worthy of a higher cause, it has multiplied commentaries about itself— as supports to a fragile existence. Never in the history of art have so many texts appeared which are supposed to

interpret, elucidate, substantiate and justify art.

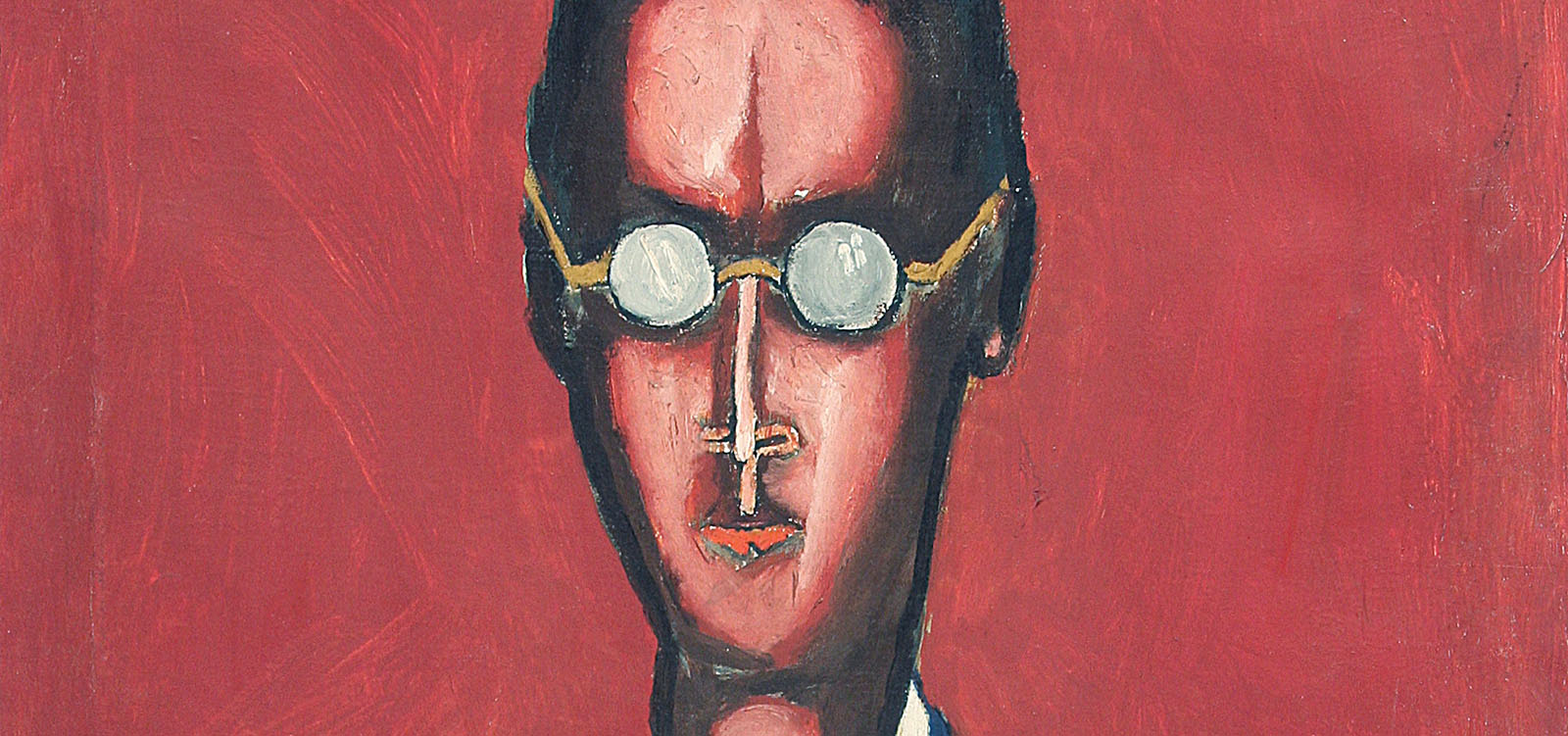

In this ocean of despair is a tiny island by the name of Jan Szancenbach. Not the only one, it is true, but indeed, it distinctly shines with its own extraordinary light. The Jan Szancenbach island is by no means subjected to any of that which is described above — to any of the elements which attempt to undermine its unyielding shores.

The whole of this island is composed of certainty, lucidity, faith and trust. Its sense and form do not undergo the slightest vacillation. Its internal life consists of canvas rectangles, continually being filled in with paint. They appear to multiply so peacefully, as though life on earth came into being simply to be, sooner or later, transferred to colourful two-dimensions enclosed by a solid frame.

Thus Szancenbach never lost hope in the art of painting, that is to say, he never lost hope in tradition as the transmission of rules, and not as questioning of their sense and purpose. His painting is the private diary of an optimist, for whom the visible world is worthy of reservation on canvas, and art is a fitting counterpart for the earth's splendour. With every picture, Szancenbach seems to say that the wonder of nature and the wonder of art should be deserving of one another. Thus the essence of his work is, first and foremost, harmony.

The antecedents of his creativity can be recognized at first glance, and were corroborated by the artist. This is namely the French School, from Cezanne, Monet, Gauguin and Bonnard to the Fauvists, as well as Polish adherents of this school: Colourists (or Capists) Pankiewicz, Cybis, and Nacht. It was no accident that Szancenbach was a pupil of Mehoffer, Weiss and Eisbisch, but in his painting it is apparent that he came after all of them. This is not only

because he creatively drew conclusions from their experimentation, but also because he, unlike they, no longer had to struggle for his vision, his concept of art. They constructed ideas and programs, carved out a place for themselves among other rules and tendencies which were stronger at the time: Impressionists against Academism, Colourists against the school of Matejko. In this struggle, ideological positions and artistic decisions had to become more

stringent. Due to the altercation with objectivity, visible reality underwent systematic distortions. During the dispute with Historicism's thematic emphasis, the deeper sense of the picture was lost, changing into a half-abstract and fabulous spectacle of pure-painterly techniques.

Szancenbach, like many others, came when everything was in readiness. He could immediately take advantage of complete freedom, which the older masters left as their legacy. He didn't have to make choices in regard to an opposition; it was sufficient to choose to continue along his own artistic path. Harmony between the visible world and the painter's material could thus reach total equilibrium. There was no longer anything to prove: Cezanne no longer had to elongate plates or tilt trees, nor Gauguin deform figures, nor Cybis spread the same, uniform layer of impasto on a vase of flowers as on the background.

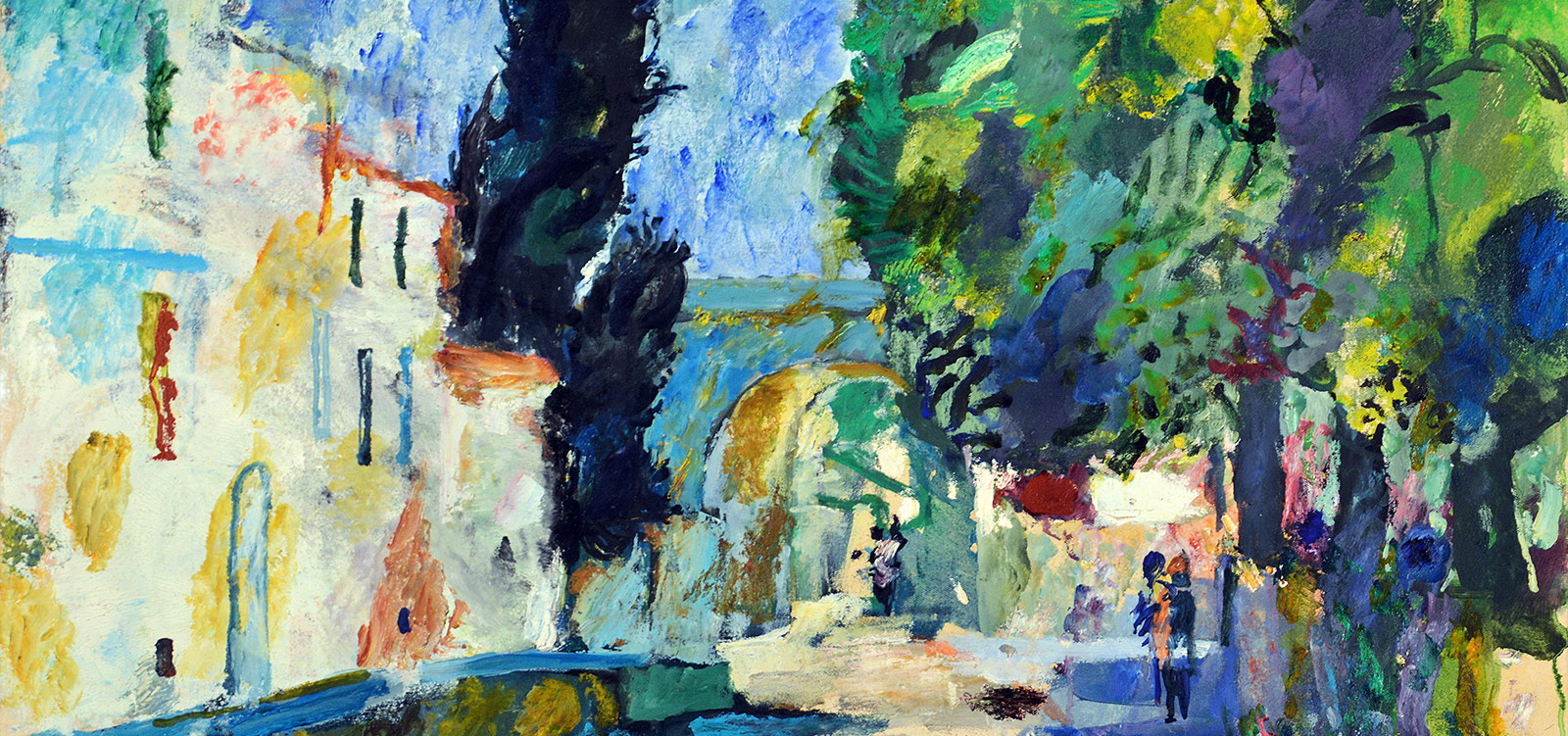

Thus the subjects in Szancenbach's pictures are just as though they were formed by nature or man. Colour is not bound by any doctrine: when necessary, it can be localised, but not imperatively. A violin can be red, however a lemon always remains yellow, and a watermelon pink with black, not green seeds.

Landscapes (seashore, mountain slope, lake, city street), still lifes (flowers, fruits, shells, crabs), interiors (studios, window and table), and portraits (woman, dog) never cease to be that which they are: simply pictures of worldly objects. In regard to nature, there is as much painterly conceit as humility.

Szancenbach's pictures are not dramatic; the desire for harmony precludes drama. Perhaps certain ones ... where the very aura of the landscape is conducive to more impetuous moods (Norwegian fjords, rain and snow in the Tatra Mountains), and certain still lifes with unexpected accumulations of reds and purples.

Another matter is that Szancenbach managed to find harmony in art rather than in the real world. It is no accident that his still lifes are the most harmonious — composed by the hand and will of the painter. Each of the pictures thus, to some extent, embellishes reality; raising it up from the commonness of everyday existence to the ceremonial character of the painted likeness. A garden is more colourful, an interior brightens, fruit in a basket glows with the radiance of eternal freshness. Even dark paintings, in umbers, ochres and murky greens shine with an internal light, more intensely than the world in its natural gloom.

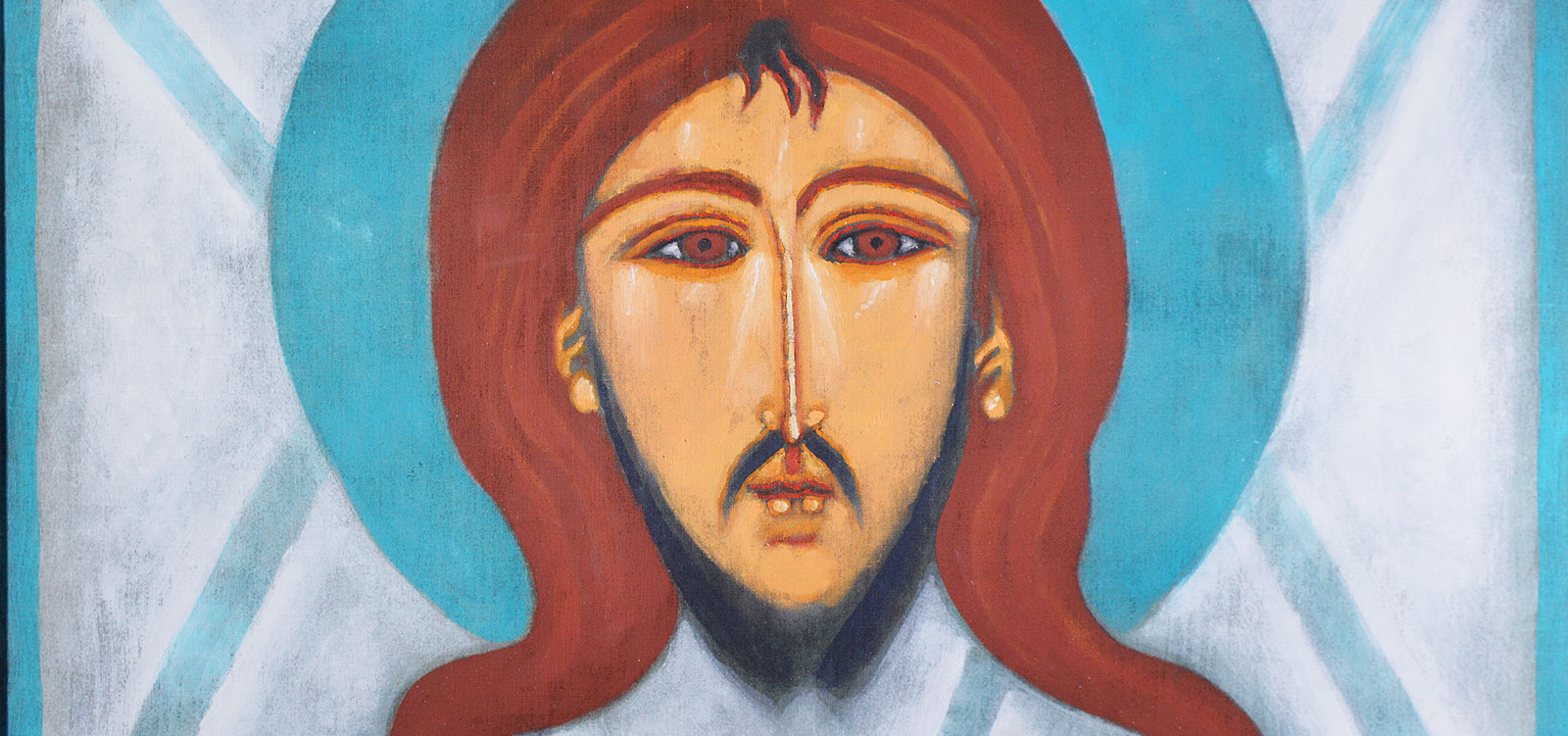

All of this is not only because Szancenbach preferred vivid colours, clean, sometimes daring, compositions on the border of flamboyant vulgarity, though never crossing the invisible, but palpable bounds of good taste. For art simply ought to be better, lovelier and wiser than the world. This is obviously pure banality, whether banality of art - or banality of language. What kind of courage is needed today to echo the very banal words of Norwid, that art is a form of love?

Szancenbach painted this form continually.

Tadeusz Nyczek