Investing in Art - The Art of Investing

We create art collections

Art Consulting

Arranging art collections

Cataloguing collections of works of art

Consevation of works of art

Monotyping: a planographic printmaking technique. A multicoloured composition is prepared on a polished metal or glass plate using slow-drying oil paints or printing inks, sometimes crayons; it is then applied manually onto moist paper to produce a single print only (called a monotype) because the paint or ink (which is not fixed in any way to ensure durability) is almost wholly transferred from the plate to the paper. Invented in the 17th century, monotyping reached its peak of popularity in the 19th century. Today, a variety of this technique is used which involves placing paper on a metal plate covered with printing ink and drawing on the other side of the paper sheet with either a crayon or a sharp or soft utensil; the resultant print resembles a lithograph, is what the Polish Dictionary of Fine Arts Terminology has to say.

This is true but not complete as it refers to technical issues only, whose role is but auxiliary.

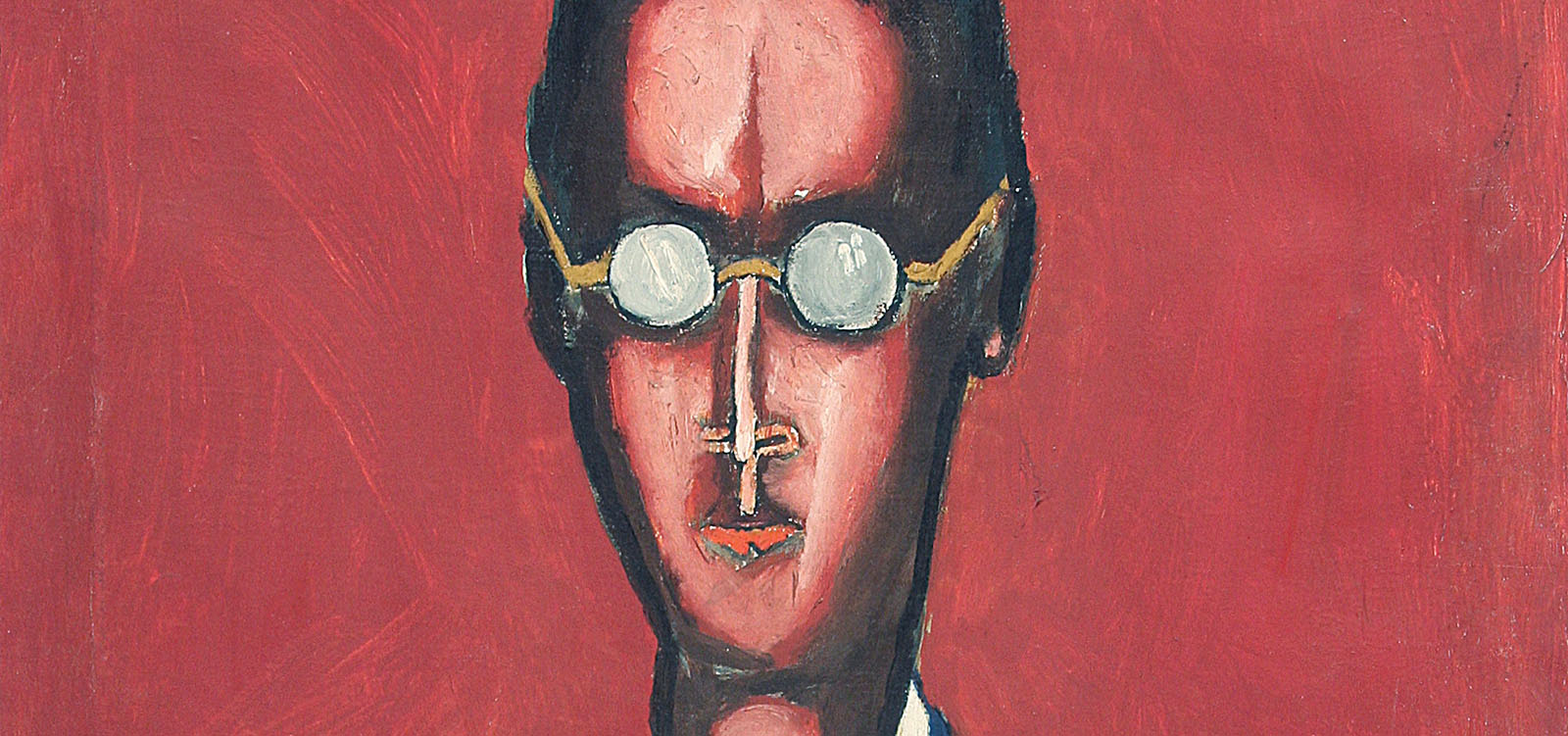

Although classified as a form of printmaking, monotyping is an autonomous discipline governed by its own unique laws. It is not printmaking per se as only a single print is obtained from a previously prepared plate while the conditio sine qua non for printmaking is repeatability, the ability to make several identical copies. It is not printing either, although it does resemble it sometimes; nor is it drawing, despite the fact that making a monotype often involves drawing. What is this odd technique then and, above all, what purpose does it serve? Why do painters of the stature of Grzegorz Bienias undertake the effort of preparing a printmaking plate instead of standing in front of an easel with a palette in their hand and indulging with abandon in the carefree joy of creating on the spot, in incessant dialogue with the emerging work of art, having the possibility of correcting any wrong decisions as they go?

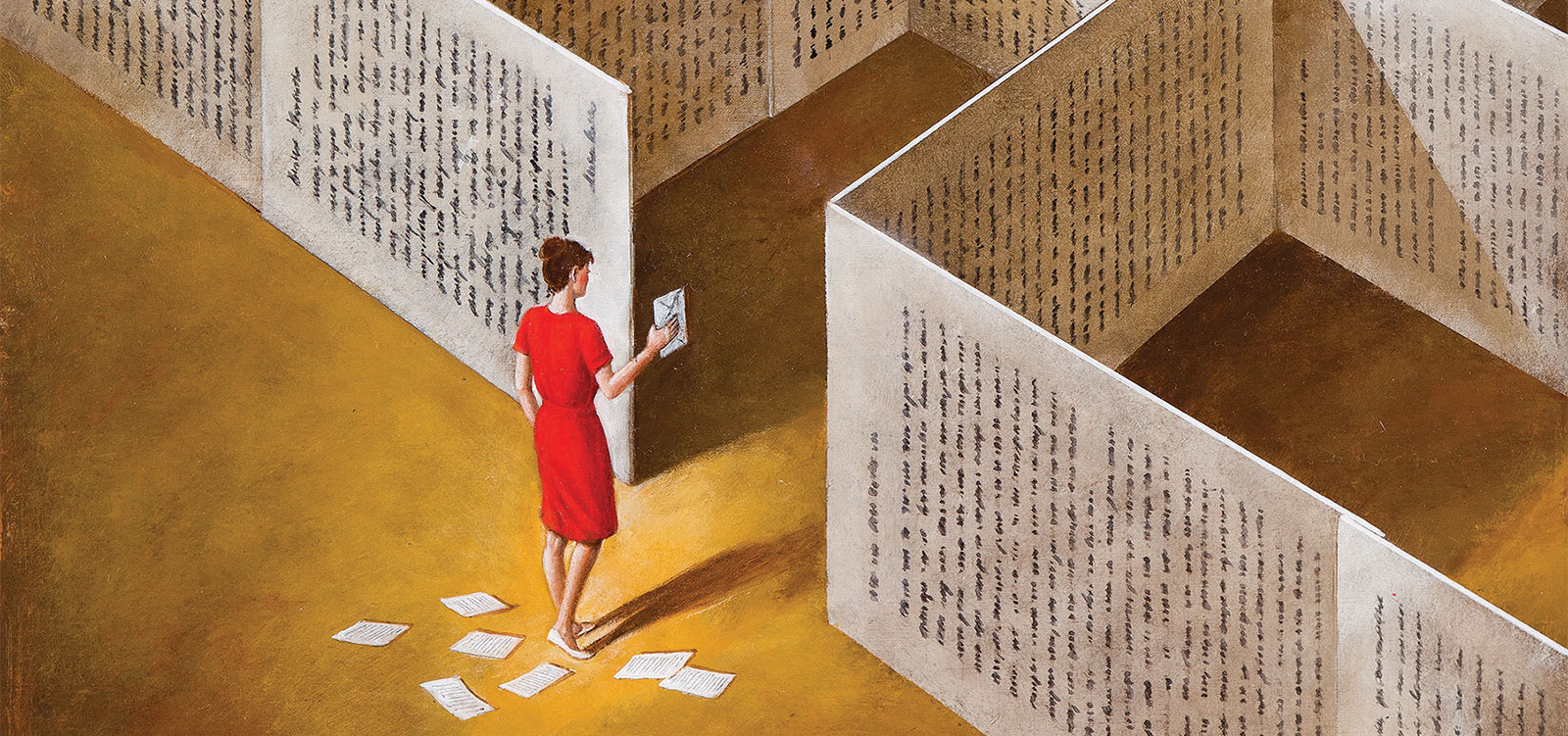

In their most intrinsic essence, Bienias' monotypes combine drawing and painting into a coherent whole. This statement, so simple, is actually very complex and abundant in implications. Namely, drawing - as Federico Zuccaro wrote centuries ago - is "neither matter nor body; it is rather an idea, an order, a term, an object of the mind; it is understanding and desire." It is thus the emotionality and mind of art.

And then, the paint stain, its colour and contrasts, are the heart of art, its feeling and intuition that is inseparably bound to it. Colour, and light which is one with it, are magic, eluding the control of the mind, which they strive to dominate instead.

Grzegorz Bienias' monotypes are a fascinating example of translating thoughts into feelings, which by the way may be commented upon with the words of one of the most outstanding translators, Tadeusz Boy-Zelehski, who is known to have said with tongue-in-cheek solemnity that a translation was much like a woman: "if it's faithful, it isn't beautiful, and if it is beautiful, then it must be unfaithful," because the mind, together with its logic and strive toward maximum clarity of formulation, remains indeed in an obvious opposition to emotion, characterised by the inclination to pile up means of expression and dramatic contrasts.

The roots of Grzegorz Bienias' art go back to the classical principle of docera, premovere, delectari - to teach, to move, to entertain. These inclinations are reflected in his study - light, spacious, downright ascetic in terms of furnishings, so different from the crammed ateliers of grand masters of drama, where - as in the case of Matejko - suits of armour, delia coats, silks and damasks were shown off amidst a multitude of other props. The only decorations of this study are copies of ancient sculptures, a remembrance and model of the ideal of art that St Augustine, the holy bishop of Hippo and a superb aesthete in one, wrote about: "The mind has noticed that it is pleased by nothing except beauty; in beauty, by shapes; in shapes, by proportions; and in proportions, by numbers."

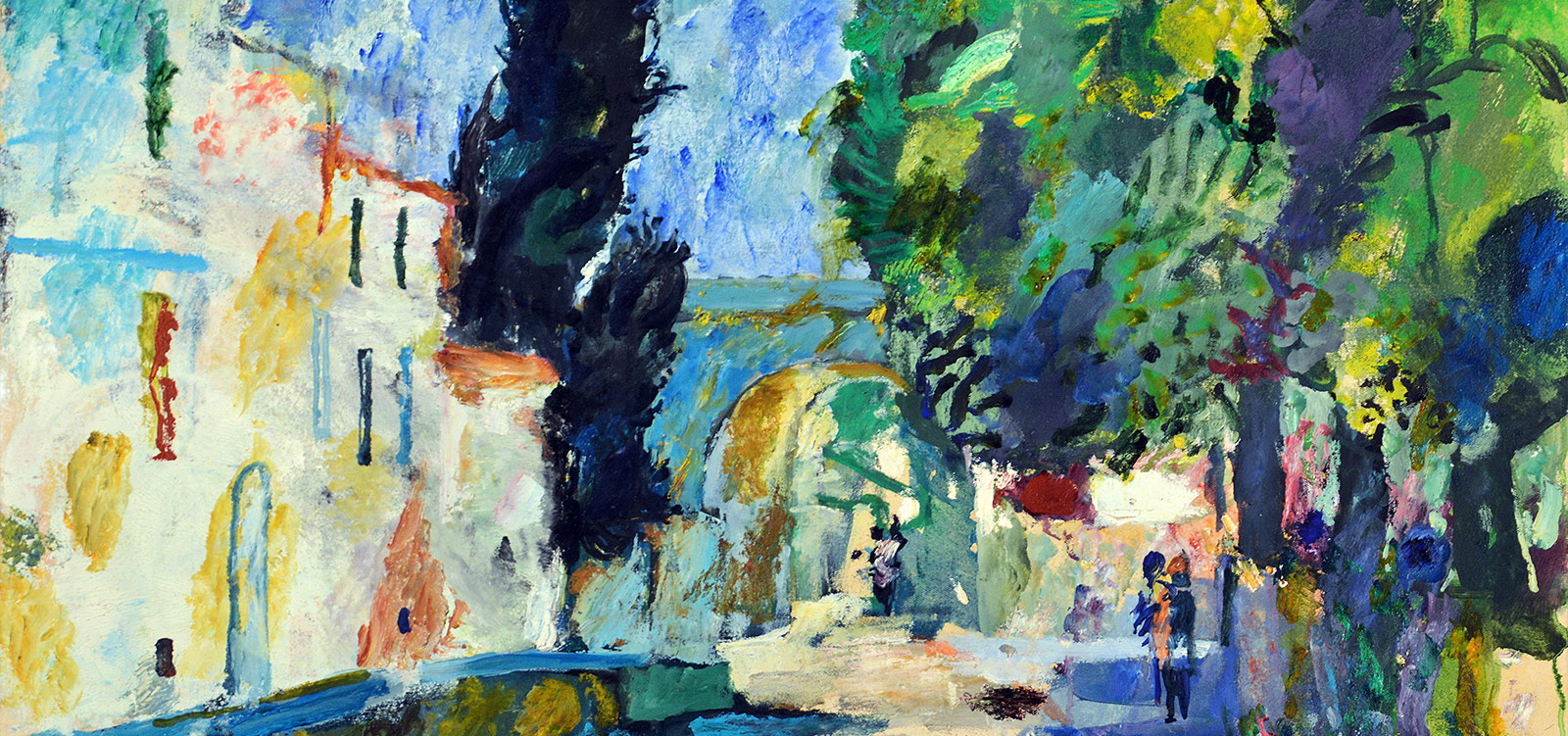

Remembrances of antiquity are also the source of the artist's monotypes: overlapping images, fragments of landscapes full of felled columns and monumental horses. And people, contemporary but of classical proportions and equally classical calm. They arise out of remembrances steeped in the spirit of the ancient temperantio, the serene moderation and the innocent - because natural - eroticism of a Mediterranean idyll, so typical of it. The impression of calmness is intensified by the composition, based on the ideal harmony of vertical and horizontal divisions, in which even an untrained eye is bound to note the perfection of the "golden cut", also referred to as the "gates of beauty". An ideal as current in the Greco-Roman antiquity as it is today, to mention merely the group of great avant-garde artists known as Section d'or, with Picasso as the most prominent figure.

The reaching of decisions and final solutions in visual arts is also based on an old method tried out by generations, namely that of Kant and Schopenhauer, postulating the a priori status of intention in relation to a work of art.

Bienias puts his memories of Mediterranean trips in some order first and only then does he make his sketches: lots of fragmentary sketches which he subsequently transfers to paper spread on the wall. And later still, he starts work on cardboard placed on a plate of acrylic glass covered with inks or paints. Finally, he lifts the cardboard and sees the monotype. In actuality, however, what both he and we can see is a transposition of drawing into painting, and of logic into emotion; of what is bright and clear (and therefore Apollonian) into what is dark, mysterious, unverifiable and unpredictable (and thus Dionysian), the terms that cover our conscious and subconscious, about which Breton, the initiator and theoretician of surrealism, writes that what is more important than producing works of art is "lighting up the undiscovered part of our being, whose whole beauty, love and virtue, hardly known by us, shine with intense brilliance."

Grzegorz Bienias' monotypes are beautiful and are works of art, and at the same time they light up, as Breton wanted, the unknown parts of our being. It is for this reason that they should be viewed and analysed on both sides. And induce us to reflect: in the recto and the verso of them, in their interdependencies existing in spite of the seemingly polarised discrepancies, aren't we finding ourselves and our innate dichotomy of perception of the phenomena that surround us and thereby the origin of our deeds?

Grzegorz Bienias draws, makes prints and monotypes, and he paints, combining - in his hands and imagination - no fewer than four artistic disciplines, together with their respective means of expression.

But this is only seemingly so. In fact, his art forms an overlapping and inseparable whole. A drawing is an introduction to a print or gets transformed into a monotype, while the latter provides the basis for oil paintings. The circle becomes full. The disciplines coexist on equal footing, submitted only to a single paramount common goal - artistic expression, in the metaphorical and literal meaning of the term.

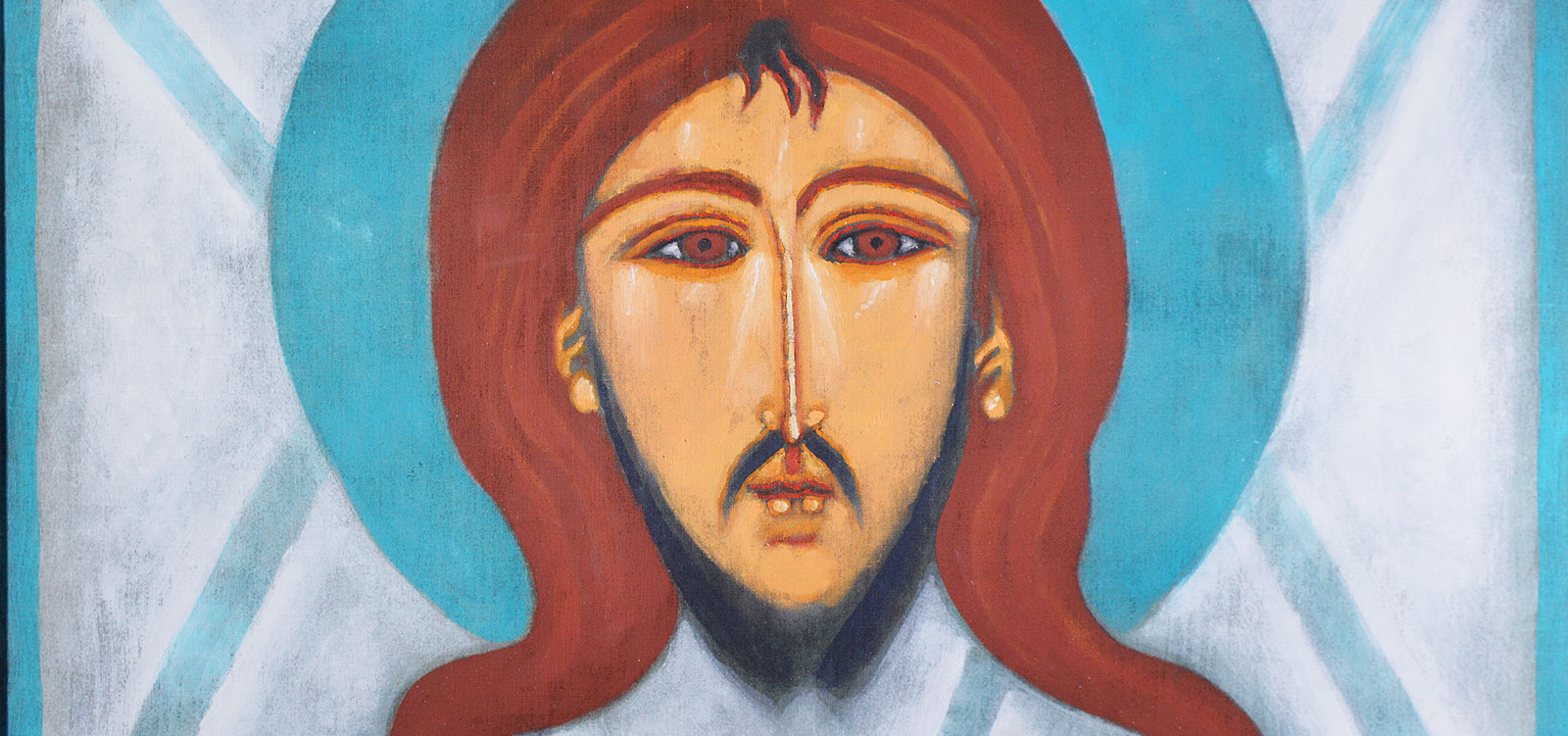

Because Bienias enjoys speaking and he can do it too; he likes to tell stories of things great and small, serious and frivolous, with a gusto of a late-Gothic artist and a unique skill for combining the sacred with the profane, sublime philosophy with attractive carnality. On equal footing and in a natural relationship with each other. But at the same time, with him, everything is an element of composition rather than redundant garrulousness.

Bienias' works do not strive for synthesis. They are a synthesis because - to paraphrase slightly Bergson's statement about philosophical intuition determining all of a philosopher's thoughts - Bienias has been endowed with exactly such painting intuition, a priceless gift. He has also been endowed with a gift for synthesising tradition and modernity within the appropriate understanding of the latter, in his entirely modern treatment of stain, line, colour and their juxtapositions as autonomous means of expression; equally modern is his elimination of details without diminishing the richness of the whole; and last but not least, the atmosphere of his works is modern too.

What, however, is timeless is their capacity for attracting or even fascinating. And that is the most important thing about them.

Jerzy Madeyski